|

"Go where people sleep

& see if they are

safe...."

My

travels with a nomad

by Anita Roddick

Last year I crossed the great

divide, travelling through rural areas of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama

and Georgia for my first look at extreme poverty in America. To be poor

anywhere is always hard, but poverty in America, in a land of such plenty,

seems harder, shocking in its incongruity.

Wealth can make people insensitive.

I've always promised myself I would never let that happen to me. Journeys

like this provide me with an antidote to comfort and complacency. They

help illuminate the current state of human affairs. But I needed the right

guide, someone who can take me straight to the heart of this forgotten

stratum of society.

I

found a guide in Jacob Holdt, a vagabond photographer. I heard about him

through a staff member at The Body Shop's U.S. head offices in Wake Forest. I

found a guide in Jacob Holdt, a vagabond photographer. I heard about him

through a staff member at The Body Shop's U.S. head offices in Wake Forest.

Born in Denmark 40-odd years

ago, Jacob has spent the last 20 years roaming America, photographing

the rural black communities in Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia

where he made his first friends.

In the early 80s he began

to share these photographs with American university students, revealing

their country's other face to them. In addition to the slide presentations,

he also conducts three-hour workshops on racism. He has visited over 270

American campuses and continues to lecture all over the world.

A gentle force

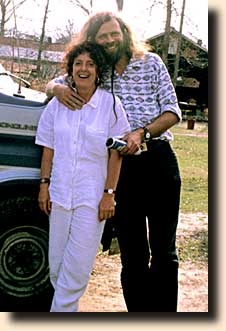

I had never met Jacob before

this trip. I was scheduled to give a talk in New Orleans and Jacob was

journeying to meet the people he had spent time with over the last twenty

years.

Together we visited shacks

and prisons cells in the forgotten underbelly of America. When we met,

the first thing I wanted to do was hand him a bottle of Brazil Nut Hair

Conditioner. His hair was as rough as straw and he had a long, plaited

beard which he rolled up when he went into the cities.

I quickly learned that Jacob's

personality was aggressively passive. If ever he was in adversarial situations,

he would gently talk his way out of things. Once, when every inch of our

truck was filled with wayfarers, itinerants and hitchhikers who would

normally strike fear in any of us -- Jacob never passed anyone by on the

highway - I studied how softly Jacob spoke and how intently he listened.

In our society, gentleness

is often viewed as ridiculous or insincere. Jacob showed me that nothing

is as powerful as gentleness or as persuasive as treating a person with

respect and kindness. This is how he has survived the hazards of the life

he has spent gathering the stories of the marginalized and the poor.

The power of hate

What I saw with Jacob astounded

me. I saw communities that had been excluded from society for generations.

They were sinking deeper and deeper into poverty and hopelessness under

the weight of structural racism. The hope for change, and the optimism

that I felt during the sixties when we campaigned for racial equality

had disappeared. The longer I travelled with Jacob, the more I started

to believe that there was no more hope.

I also saw the effects of

the incredible power of television -- how television is just like a pacifier

to the mind. A pale blue light flickered in the broken down shacks 24

hours a day. It seems that we have all become part of a media culture,

designed to perpetuate the myth that material wealth defines self-value

and self-worth. My insight is that racism and poverty cast the longest

shadows over America today.

While we travelled in the

truck Jacob and I talked long and hard about racism. I used to be convinced

that colour was not important in my relationships. I am constantly checking

myself: Do I understand the definition of racism? I think racial prejudice

is like a hair across your cheek -- you can't see it, you can't find it

- you just keep brushing at it with your fingers. It frightens me, and

never more than when I see the impact it has on peoples' lives.

Poverty shames us all

Poverty in the face of such

affluence is scandalous. If companies invested in communities in need,

families could work together and skills could be protected. I tried to

see if The Body Shop could set up a small-scale economic initiative within

the communities that we visited.

Although this particular initiative

failed, I believe more strongly now, more than ever, that we must continue

the fight for community-based businesses. It is these micro enterprises,

these informal networks out there which form a rag tag front line in the

worldwide struggle to end poverty.

The Body Shop magazine distributed

to stores and customers worldwide.

October 1995, Gobsmack

|