Book 4, pages 49-51

The Native American uprising in Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1973 became a

turning point for me. We on the American left had constantly romanticized

the use of armed force. Many of us were tired of demonstrations, so the leap

to armed struggle was not great. But Wounded Knee was a depressing

experience. In our romantic intoxication we had not given much thought to

all the psychological problems one is exposed to when lying in trenches in

snow and sleet for weeks. I saw so much discord and infighting among the

Indians that I don't feel much inclined to talk about it. Also, they treated

us white helpers almost as slaves.

We helped them smuggle weapons and ammunition into the supply camp for the

rebels, who at night carried it on to the trenches around the occupied

village of Wounded Knee - an operation that took many hours since the FBI

frequently sent flares up. We helpers were not very used to shootings, and

it took a toll on many when the bullets flew over their heads. On one trip I

lost my bag with both passport and camera, and a car was made available so

that I could go and try to recover my things. As it was now daylight, I knew

I would be discovered by the FBI and on the way back I was duly chased by an

FBI car at a hundred miles an hour.

I managed to elude them in the village of Porcupine when I hid myself in a

funeral procession for an Indian who had been killed during the struggle.

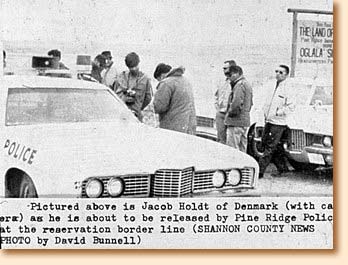

Later, on another occasion, I was arrested by the FBI; I had a short-hair wig

on, because the day before I had been arrested by them and thrown off the

reservation. I had hoped that they wouldn't recognize me. When I was

transferred to an Indian jail, I managed to persuade the Indian policeman to

release me by giving him a bad conscience about his working for the government.

Well, I don't think these external experiences were the reason I felt defeated,

rather, it was my more intimate experiences. I had become particularly good

friends with one of the leaders in Wounded Knee, a Sioux Indian whom I will

call X. I had driven with him and a white lawyer from Rapid City. When we got

to the reservation, they did not stop the car and we were shot at by the "goon

squad". I was shocked, but later found out we had been carrying an arms

consignment in the trunk. We dropped the lawyer off at the camp where the

Indians were in the process of negotiating with Washington the handing-over of

the now half-rotten body of one of the Indians killed at Wounded Knee. We then

drove to the Rosebud Reservation, where X suggested that we stay overnight with

his aunt. She let us sleep on a mattress in her kitchen, and I began to stretch

out a blanket on the floor so that X could have the narrow mattress. But he said we should share the

mattress and gave me a long explanation on how, according to Indian custom, it

was impolite to refuse an invitation. As we lay there on the mattress he

whispered mysteriously to me about the spirits, and the prairie wind moaning in

the eaves added extra atmosphere. He gradually fell into an ecstasy and

couldn't understand why I was not able to see the spirits in the darkness. He

started shivering violently and held me tighter and tighter. After a while his

trembling lessened a bit and he began kissing me - big wet kisses.

Only then did it dawn on me that he was homosexual, but a kind of homosexual I

had not met before. Although he had a hard-on, he wasn't after sex and didn't

take his clothes off. He just wanted to make love on a "higher plane" and

spiced it all with spirits and demons in such a way that even today I still ask

myself if he was really on the level with me that night.

The next day he took me with him to the supply camp where we spent the

following week. Here I saw a completely different side of him as one of the

camp leaders, and he never in any way showed that he liked me, so I soon

concluded that Indian culture strongly suppresses homosexuality. But he treated

me better than the other whites were treated and as his friend I soon got

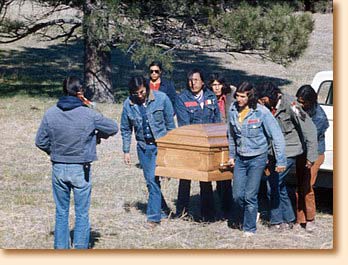

special assignments. Thus it was he and I who would drive the truck with

Eastlake's coffin and Rosemary, Eastlake's eight-months-pregnant widow. We had

sat up all night in the house of the medicine man Crow Dog, holding a wake over

the body. Both he and X had offered long Indian prayers by the coffin. The

tears streamed down X's cheeks all the while and that which I had perceived on

that other night as hypocrisy now seemed quite different. We took a green

medicine that had a powerful effect and I let myself be carried away and stood

up, like several others, to make a speech by Eastlake's coffin. I compared

Nixon's slaughter of the Indians in Guatemala during the Eisenhower regime with

his present genocide here in Wounded Knee. I was the first one who tried to put

Eastlake's death into an international context, and it made a certain

impression, I was later told.

Because of the many telegrams coming in from all over the world (even China and

Russia), we had felt the whole time that we were in the midst of something of

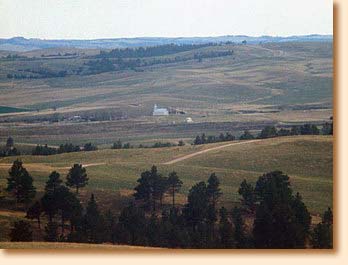

historical importance. But the next day, as we stood out there, in the desolate

hills where only a few scattered firs grew, lowering the coffin into the hole,

we nevertheless felt strangely forsaken.

I felt an immense emptiness and for a moment all

historical significance vanished. I caught the eyes of a young Tipoix Indian

woman who had hitched to Wounded Knee from Minnesota in red clogs in order to

fight. She was extremely beautiful and we started flirting with each other as

our eyes met over the coffin. No sooner had we all smoked the peace pipe and

scattered the ashes over the casket, as is the custom, than Bobby and I began

spending all our time together. We tried to keep our relationship secret, as it

was not acceptable for a red woman to be seen with a white man.

All the same, X soon got wind of it and was furious; however he was totally incapable of looking me straight in the eye and therefore dressed me down indirectly. He called the whole camp together and made a long speech about the promiscuity flourishing in the camp and how we had to respect the Indian traditions and be in mourning with dignity after Eastlake's death, etc., etc. He then called all the Indians together to discuss whether or not the whites ought to be expelled. I later found out that there had been a majority for it, but that X had then backed down and demanded that we stay. The long and short of it was that X had fallen deeply in love with me and I am absolutely sure that that was the only reason the whites were allowed to remain in the camp. Slowly I began to realize how in love with me X was. As he was inordinately jealous of Bobby, I got orders to sleep in the tent of honor in the future, along with himself and Rosemary, who was in mourning. I was very, very moved that I would be sharing the tent of the widow of one of the first Indians to be killed in the first Indian insurrection of modern times. In my revolutionary intoxication I felt that I had landed right in the middle of a historic focal point. I had already become good friends with Rosemary because of the speech I had made over her husband's body, and I had very strong feelings for her - eight months pregnant as she was. But from there to actually living with her and the leader in the tent of honor was nevertheless a leap. Naturally I felt a certain pride toward the other whites about being "promoted" to Rosemary's teepee.

With this historical consciousness

of my own situation I was not at all prepared for what happened in that very

tent. Rosemary lay in the tent's only bed, chatting with me in the glow of the

lamp, while I lay on the ground. She became more and more lively and seemed

more and more overwhelming. Then all at once she asked if it was okay if she

lay down beside me. I was completely taken aback, and before I could answer,

she had climbed down to me and laid herself up close to me in my sleeping bag.

I didn't know what in the world to do and lay completely stiff. I have often

run into similar situations, but this was some-thing very different, and to

even think about sex in this situation was out of the question. It was only two

days after her husband's funeral - the husband whose child she lay with there

against my stomach. I was shaken and shocked. All my romantic and revolutionary

ideals fell with a crash. (I have since been told that this behavior is not

abnormal for a person who has just lost a husband or wife.) I was thinking of

all the telegrams of condolence pouring in to us from all over the world, and I

don't know how I should have managed the situation if X had not come back from

a meeting just then. X became my rescuer. When we heard him coming, Rosemary

got up in her bed again. X blew out the light and lay down beside me, just like

the first night at his aunt's house. Since then he had not dared to show me any

sign of affection. Although ordinarily I greatly prefer sex with women, I must

admit that when be began to kiss me that night, I felt as if he had just saved

me from a very, very embarrassing situation.

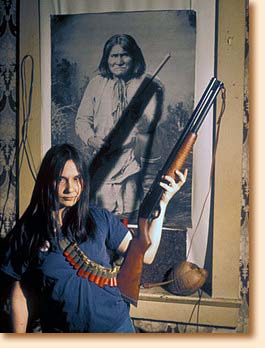

Please note: This story is difficult for me to illustrate since my camera broke in Wounded Knee and for months I did not have the money to repair it. Most of my pictures were over-exposed such as this warrior.

A few days later the warriors sneaked out of Wounded Knee and the rebellion was

over - but not for me. Many of the weapons were buried in the hills around the

camp, after which the Indians fled and spread out all over the U.S. and Canada.

Two of them stole all the money in Crow Dog's camp and took off for Oklahoma

with it. Bobby had to leave before we got a chance to say goodbye. X was

watching me day and night, and suddenly I again found myself in a crazy situation. He was so much in love with me that he

wouldn't let me leave; but he dared not show it and therefore gave orders to

the guards around the camp that I was not allowed to leave it for "security

reasons." He said to me that I had taken pictures that could fall into the

hands of the FBI, but to the guards he only mentioned the unspecified "security

reasons," and suddenly I sensed hateful and suspicious eyes every-where, and

every time I came close to the perimeter of the camp I immediately had a couple

of rifle barrels pointed at me. My situation became more and more desperate, as

I couldn't explain the actual reason to any-one in the camp. I didn't want to

compromise X, and any-way, if I had told people that their great leader

wouldn't let me leave because he was in love with me, they would not have

believed me. I was a prisoner of the Indians without anyone knowing why. It

became unbearable, and some days later I managed to escape through the

reservation and hitch-hike the two hundred miles back to Rapid City.

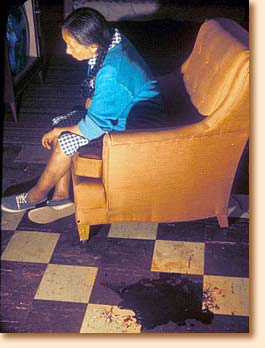

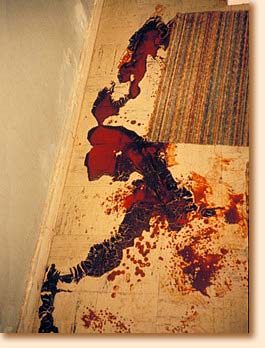

In Rapid City I again stayed with the Indian woman who had first brought me into contact with AIM (American Indian Movement) before I went out to Wounded Knee. She had nothing but contempt left for the rebels and in the evening she took me to a big fancy steakhouse, where I had the best and most civilized steak I have had for a long time. Oh, how I enjoyed being back in America! But the violence followed in my path, and one night our neighbor was murdered in the apartment downstairs as an act of revenge after the rebellion. For several days we sat together with his mother and got drunk while staring at the pool of blood on the floor, which she refused to wipe up because it was the only thing she had left of her son.

The inner violence which increasingly

characterizes Third World people as a result of their long oppression is,

however, usually not turned outward among the Indians as with the blacks, but

turned inward in the form of suicide. Perhaps our enemies, after all, saw the

Wounded Knee insurrection as just another suicide attempt? And maybe we

ourselves were influenced to such a degree by our enemy's view that we couldn't

all live up to the harsh human demands the rebellion made on us. For my own

part I had had enough of armed struggle and "armed love" and thereafter gave

myself fully to the role of vagabond. To be a vagabond is just an attempt to

give oneself fully to the individual person. But to be a revolutionary is an

attempt to give oneself fully to all of humanity. No human being is able to

combine these two attitudes, and for my own part I suffered a defeat at Wounded

Knee, just as many of the Indians did. Human beings are so infinitely weak and

small that if they are ever to become fully human they must combine these two

sides. Although almost all of us suffered defeat in Wounded Knee, Wounded

Knee was nevertheless a victory, because it was such an attempt.

Excerpts of letters

Copyright © 2005 AMERICAN PICTURES; All rights reserved.