| | |

Chapter 15

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

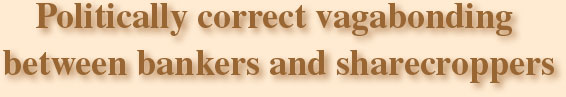

As a vagabond I can in time break out of this

brainwashing and move back to the different impact of the black community. The greatest freedom I know is thus to be able to say yes; the

freedom to throw yourself into the arms of everyone you meet.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

Yet I soon learned that there are limits - for instance for a

male hitchhiker. Foreigners usually find white American women incredibly open,

but that also makes them extremely vulnerable. It is important to let the woman set the boundaries of a new

friendship if we hope to avoid the sexism imposed on us by society.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

From early childhood we were never given the choice of becoming

sexists or racists or not, but only of trying to counteract the most negative

repercussions of our suffering.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

On the other hand I can not - as when male drivers pick me up -

just say yes to women and float along to the critical point where hurt feelings

can develop. To be a good vagabond is harder than being a tightrope walker. Students

in American universities trying to be politically correct know the difficulty of

my balancing act.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

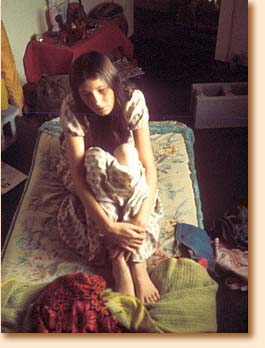

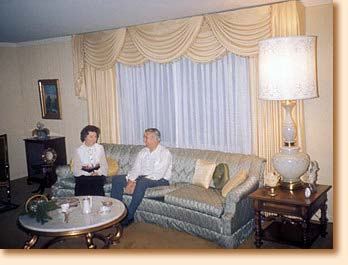

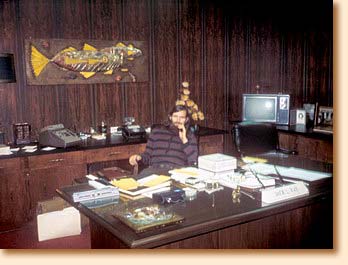

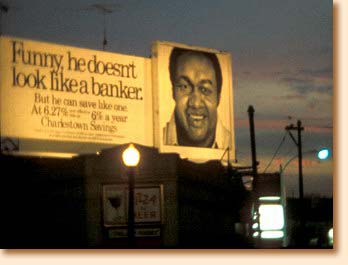

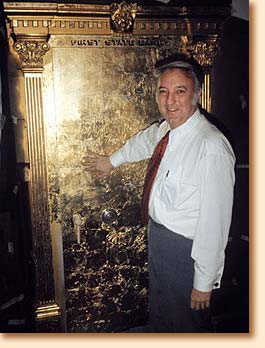

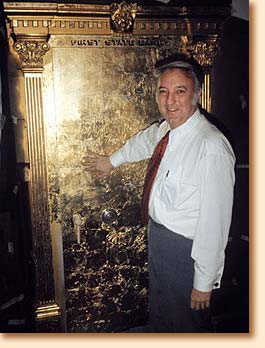

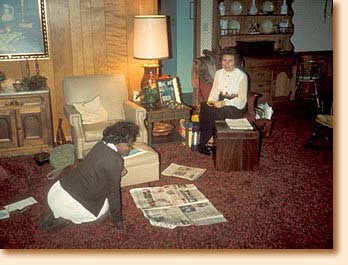

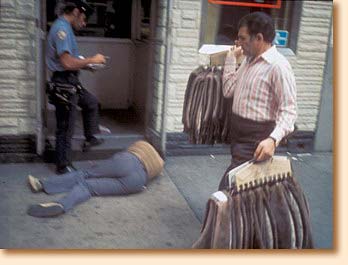

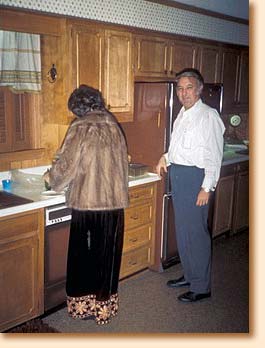

Such a balancing dilemma I faced in Alabama when I lived with a

rich bank owner. This banker was one of the more liberal in Alabama and

had hired "niggers" as cashiers in his bank, although he called them

negroes

whenever he was in their company.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

Often as a poor vagabond

I periodically got a strong desire to get an education in order to have a

career and get to the top in society, but whenever I, as here, got a chance to

live the so-called good life, it usually made me so sick that I quickly fled

out again to the highway.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

For where did all the gold, which the banker used for his luxury

home outside the city, come from?

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

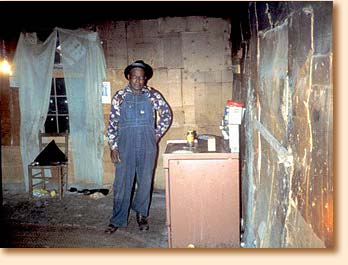

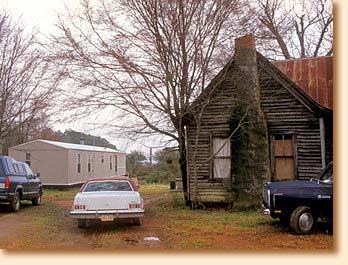

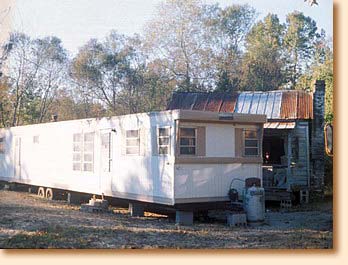

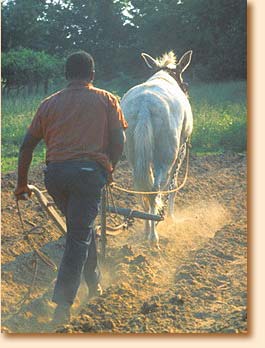

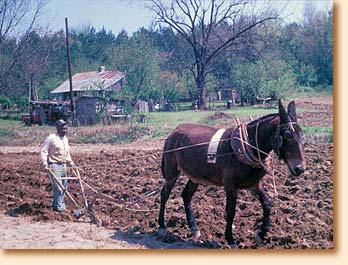

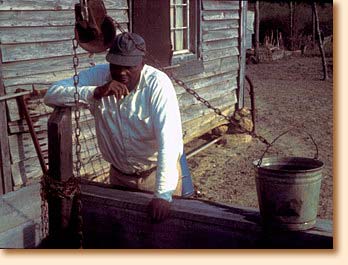

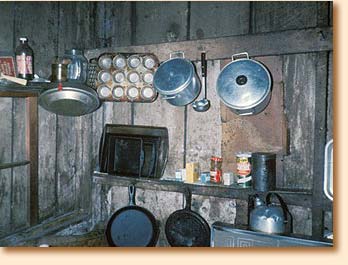

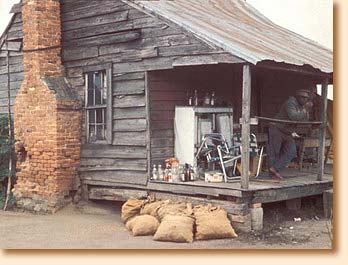

Well, he told me that he had made his fortune by giving bank loans to poor

black sharecroppers so that they could buy themselves a mule or move from the

rotten shack into a streamlined plastic trailer to join the new plastic

proletariat of more than 30 million Americans.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

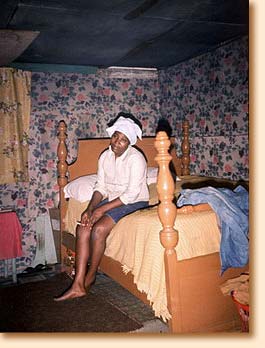

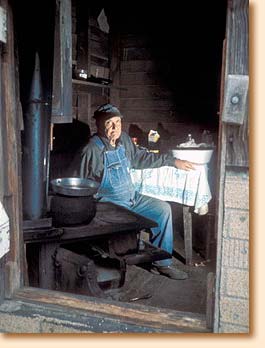

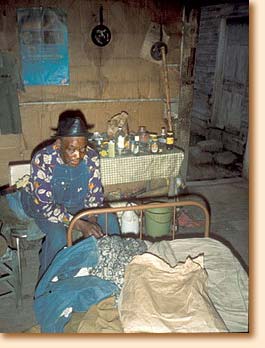

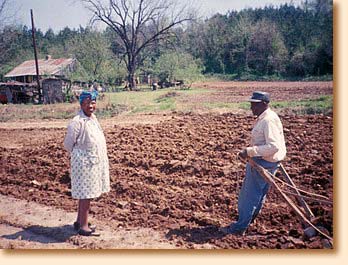

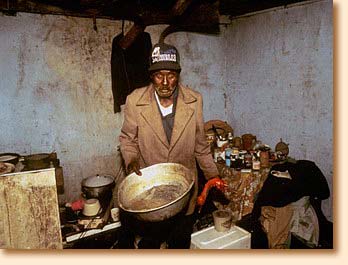

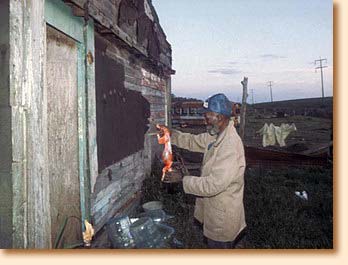

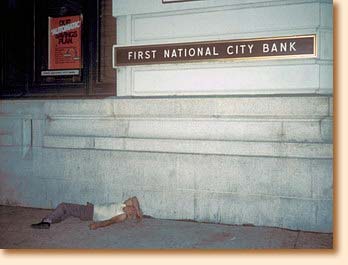

But many sharecroppers cannot even afford these modern plastic

shacks.

They have enough problems making payments for the mule and are in

constant debt not only to the bank, but also to the white landowner who owns

the fields and to whom they often must pay the greater share of their harvest,

just as we in feudal Europe paid the church and the squire.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

The system started at the end of the civil war when neither the

planters nor the freed slaves had any money. Driven by hunger to work for

little or nothing, the destitute blacks made agreements with their former

slave-owners to borrow land as well as housing and seed.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

In theory, they would share the profit when the harvest was

sold. But debt and dishonest bookkeeping usually brought the sharecroppers into

a situation materially worse than under slavery, in which the master had at

least an interest in feeding them.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The system has continued from generation to generation and on top of the

eternal debt to the landlord came the debt to the commissary store and later

the bank, all helping to create a white upper class.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

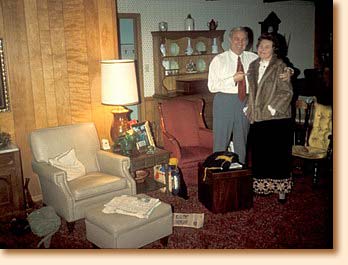

This banker in Alabama had feathered his nest so well that he

could take me on a trip in his private airplane to look at his

niggers from above.

The Atlanta Constitution revealed that such exploitation -

like the squire in European feudalism - continued through the 1990's.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

American thinking says that when people go hungry they only have

themselves to blame because they will not work.

But why then do the hungry often work harder and longer than

those who are causing their hunger?

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

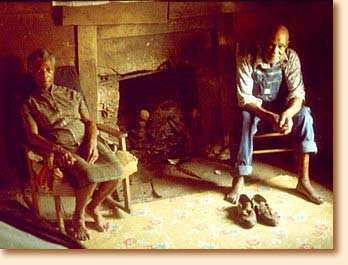

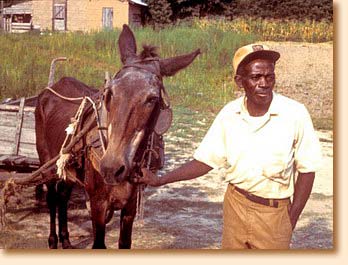

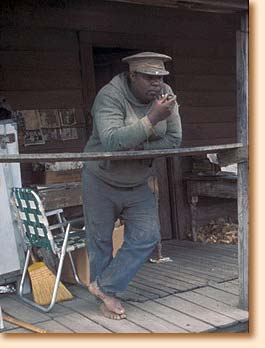

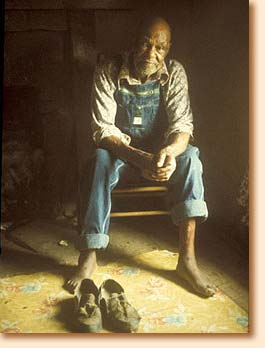

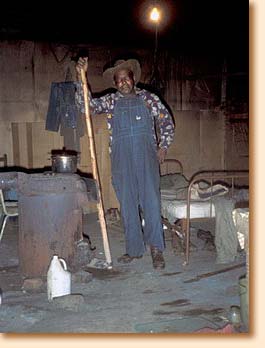

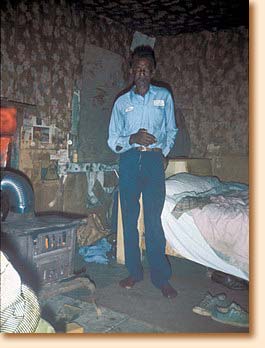

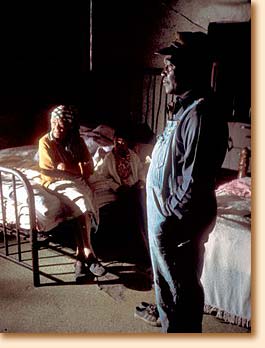

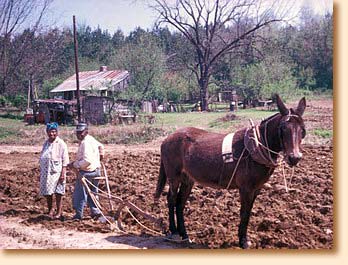

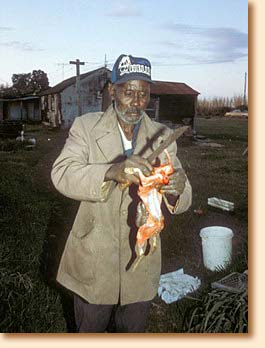

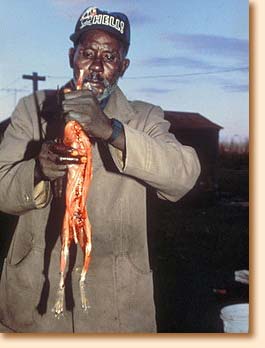

Later I visited this tenant farmer living close

by. Both he and his wife

were 78 years old and should have stopped working years ago. But he said to me:

"I have to work until I drop dead in the fields. Last year my wife got heart

trouble so now I must do the work by myself." |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

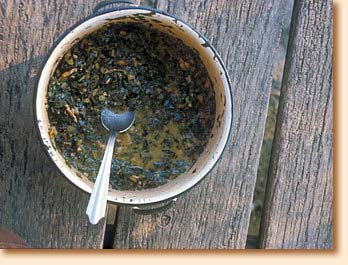

Twice a year he walked to the

local store to buy a bit of flour and a little sugar. That's all he ever

bought. I asked what they got to eat for breakfast. He answered: "A glass of

tea and a little turnip greens."

- What then for lunch, I asked. "Just turnip

greens," he answered.

- And what then for supper? "Mostly turnip greens" was

the reply. |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

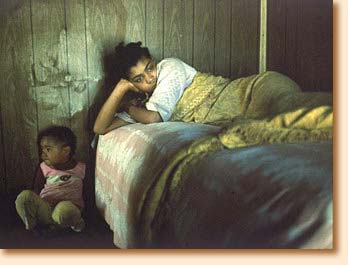

My attempts to find out about conditions for these sharecroppers ran

into an almost impenetrable wall of fear and intimidation. I had imagined that

this fear was entirely historically conditioned until one night after a visit

to such a sharecropper, on my 10-mile walk down a dead end road to my shack, I

was suddenly "ambushed" by a pickup truck with headlights turned on me and guns

sticking out. I managed to talk my way out of this situation, but little by

little I realized that such intimidation was deeply rooted in the violent

system of peonage, which traditionally has prevented sharecroppers and

farm workers from fleeing their "debt" by the use of beatings, jailings, and

murder. |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

During World War II the U.S. Justice Department admitted that "there are more Negroes held

by these debt slavers than were actually owned as slaves before the Civil War." Yet the Justice Department did nothing to prosecute these slave owners, who

even traded and sold the peons to each other. Although there were an increasing

number of peonage cases in the 1970's, it is only a few that end up in court;

and only the most cruel, such as a case in 1980 where a planter chained his

workers to prevent their escape, reach the press (and the American public). |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The more I began to penetrate this undercurrent of dread and terror, the

more I began to feel that the first part of this century has had a far more

violent influence on the black psyche than the probably more paternalistic

antebellum slavery.

I began to feel poles apart from the common white ignorance

which seems forever unable to understand why their own white ancestors could

"make it" in a short time while the blacks in 100 years of

"freedom" had been

"incapable of making it." |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

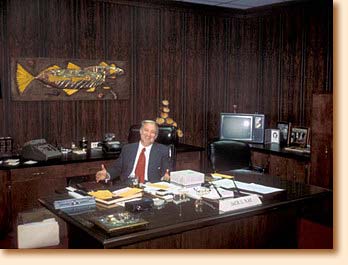

This banker, who is a recent beneficiary of this

violent ignorance, had unknowingly fit one more piece for me into the pattern

of hunger and dread I saw in the rural underclass. |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

- But often you went to bed hungry?

- Yes, Sir, more times than not. But some times people would give

us some bread or give us a meal.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

- White people?

- Sometimes whites, sometimes colored. Sometimes we would have

nothing and go to bed hungry. We went to bed a million nights hungry. Sometimes

we wanted to hunt, but were too weak to catch the rabbits.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

Racism is afflicting all countries. Yet it is more apparent in America because it is intertwined

with a ruthless class division - the greatest gap between rich and poor in the

industrial world. For without a protective welfare state here to hold our free

enterprise system in check many people are made too poor to be free to

enterprise in it. When 2 % today therefore ends up owning 80% of the American

wealth it is not hard to see where this banker's mink fur actually came from.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

The only thing he cannot buy is real happiness. And so I see again and again that the upper class try to

substitute whiskey, tranquilizers, and cocaine for personal happiness.

|

| | |

| | |

|

|

| | |