| | |

Chapter 26

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

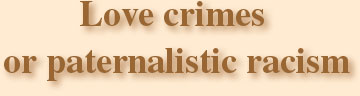

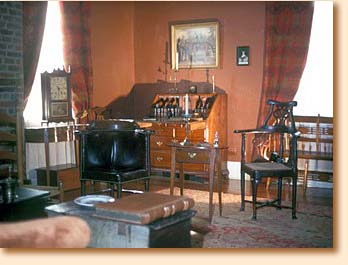

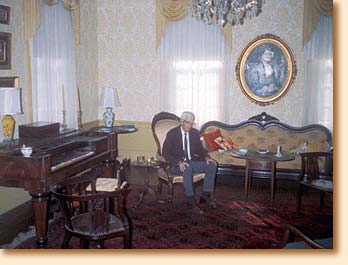

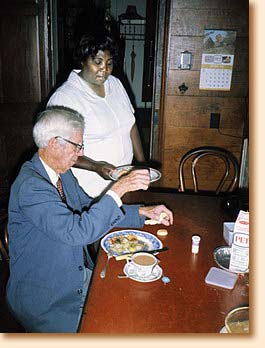

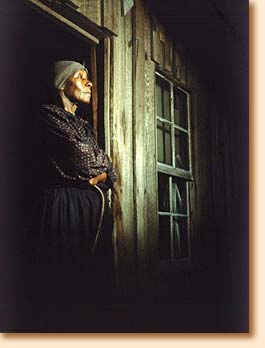

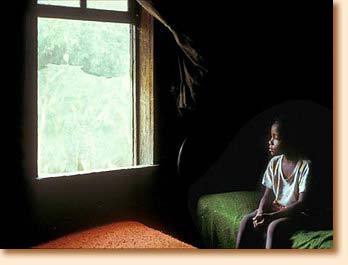

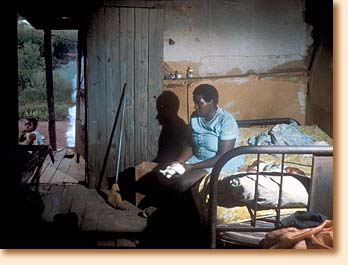

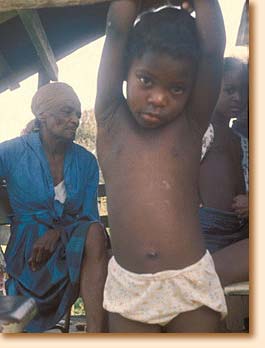

In Georgia where I lived with the Barnett family in one of the old

plantation homes, I learned about a different kind of racism, one not based on

hatred, but on a historically conditioned paternalistic love for the blacks.

Mrs. Barnett spent days taking me around to families her family had once owned

- apparently a very short time ago in her imagination (and, as I found, in the

black consciousness as well).

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

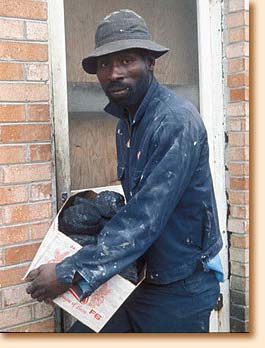

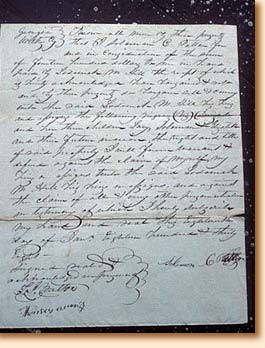

Mrs. Barnett: This is the bill of sale to my great, grandfather from Mr. Cadman

for Lucinda, her children and her increase forever. The price was $1,400.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

Mrs.

Hill (her friend from another plantation home): But you see, when they came

here they were savages, and I think instead of blaming the South like the North

blamed us, I think we deserve a bit of credit. They sold them to us and they

knew they were selling us savages. But they just kept sending them.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

And then

they began talking about our harsh treatment, but you know when you had people

working for you, you would do every-thing for them, feed them up, give them

clothes and housing and take care of them.

Mrs. Barnett: The white people would do anything for the niggers except get off

their back, as they say. (laughter) One thing is sure. We still miss them.

Mrs.

Hill: Yeah, we do miss them.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

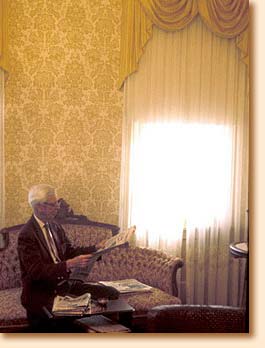

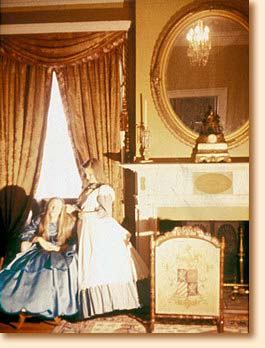

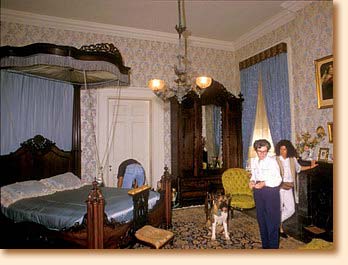

When a "house slave" came in with afternoon tea, the talk, as always in the

Southern aristocracy, turned to the follies of their servants-away for them to

maintain their paternalistic attitude toward the blacks and thus give

themselves the social distinction of previous times.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

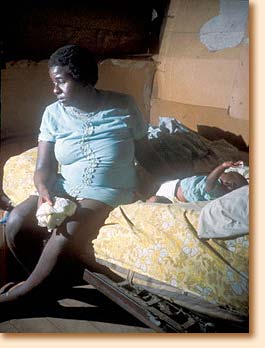

What Mrs. Barnett misses is not slaves as a work force, but the

old mutual dependence of slave and master. The fact that one could lose a slave

worth more than $1,400 through sickness instilled in the white upper class a

paternal concern and responsibility for the slaves.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

The upper class became dependent on this responsibility as a

kind of love. In Mrs. Barnett's case this love shows itself best in her great

work on behalf of black prisoners with life sentences in the local penitentiary,

- in other words, in a need to express love for a group of blacks who, like the

slaves, are not free.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

Was this the type of racism I myself was developing in this

society? Or how long could I hold on to the naive idea that as a

foreigner I could keep afloat in this ocean of racism - drowning everybody else?

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

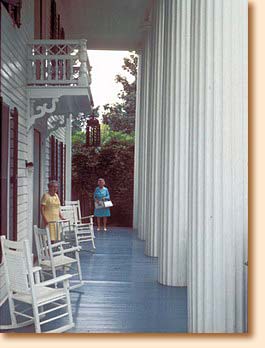

In the South I had experienced two completely opposite white reactions

towards blacks: hatred and love. Value judgments such as good and evil began to

disintegrate inside me the more I saw these peculiar white reactions as being

products of a centuries-old system. I could no longer hate these whites in

spite of their trail of destruction.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

From this moment, I could show them

respect and understanding, and doors began to open everywhere: the doors of

Southern hospitality. When I later traveled among South African whites, I met

an even more overwhelming hospitality which seemed directly proportional to a

greater class difference between blacks and whites. Just as in South Africa,

blacks in the South receive the traditional friendliness as long as they have

underclass status.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

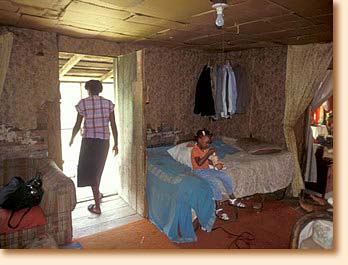

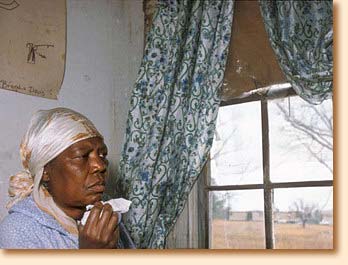

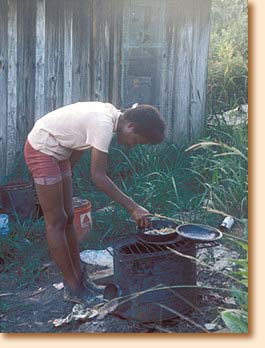

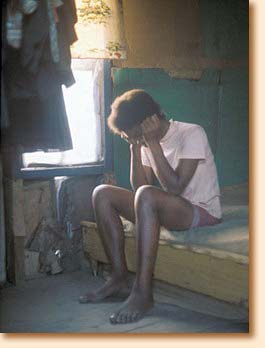

They are not paid mainly for their work, but rather for

their servility and humility, for knowing their place and being dependent.

Their passive resistance to this subjugation is seen as "irresponsibility" and

"shiftlessness" which further confirms the "necessity" of the paternal

relationship, thereby increasing white status. This artificially high status

adds to the psychic surplus displayed, for instance, in an overwhelming

hospitality and friendliness towards the individual but not the group, such as

"Negroes," "Yankees," "communists." |

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

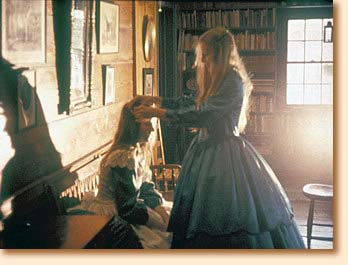

I had arrived in one plantation home with my wig

on, but as the hostess had increasingly fallen in love with me,

one night I surprised the dinner party by suddenly displaying all

my hair. The hostess burst out "I know you are a communist, but I

like you anyway."

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

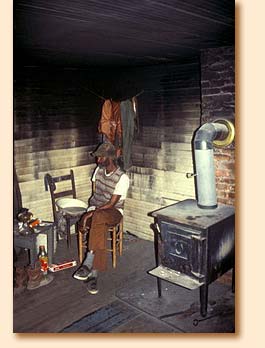

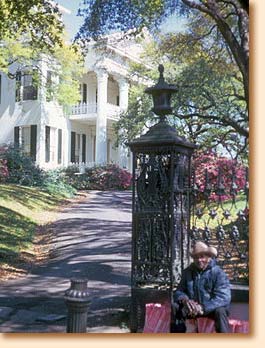

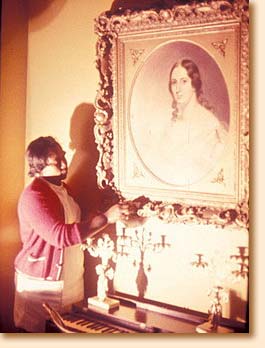

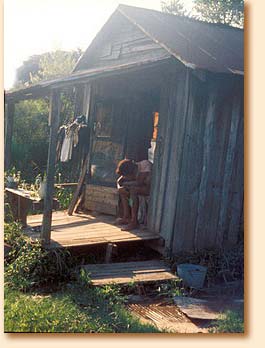

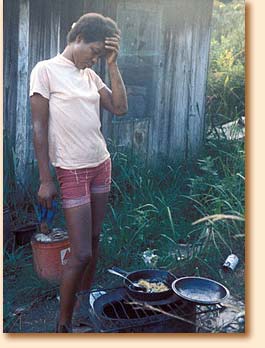

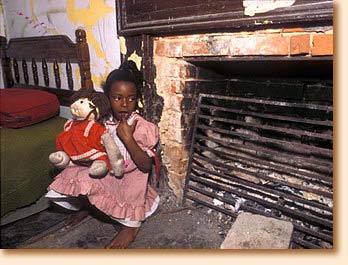

This hospitable class may not participate in white

terrorist acts, but it benefits directly from such policing. None of the plantation homes I lived in were

locked although they were filled with gold, silver, and expensive paintings

right next to some of the poorest people on earth, whom I often saw commit

violent crimes towards each other.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

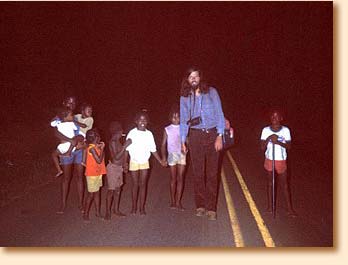

One reason I could move around in even the

most dangerous black milieus in the South without fear for my life was thus my

realization that the sense of slavery held its protective umbrella over me

everywhere. And when you are up against a system so deeply ingrained that your

"Scandinavian blue-eyed idealism" is not even understood, you easily give up

and become a participant.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

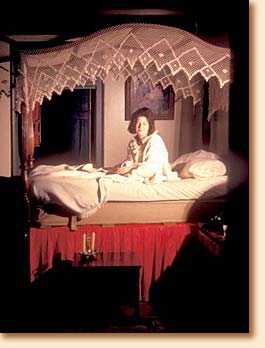

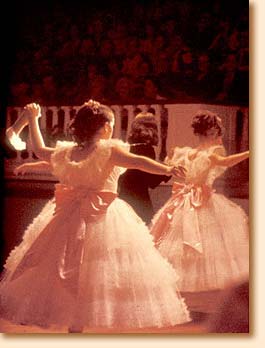

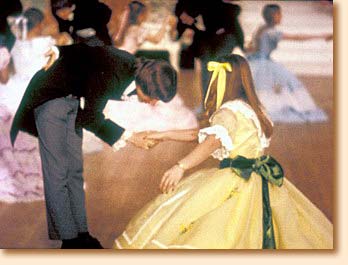

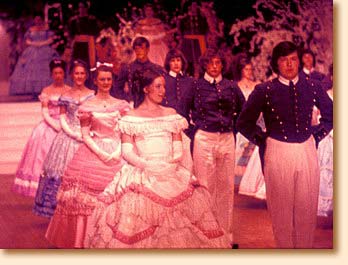

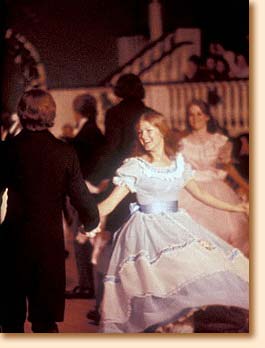

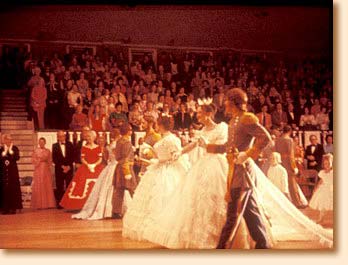

Thus I soon learned the self-crippling and basically

uncomfortable art of having black maids serve me breakfast in the canopied bed

(in a separate room from the hostess) and not committing the crime of making my

own bed. In Mississippi I saw the servants spend days dressing up the white

"belles" in antebellum gowns so we could continue the old balls of the

Confederacy, where blacks are only present in the form of a white woman in

blackface acting as

"mammy."

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I loved these seemingly stand-offish yet incredibly warm, open, and

charming belles. Yet I had to laugh the last time I came back in Natchez in 1978 and found the town

extremely upset about an article in the New York Times describing the

plantation homes as "decadent and promiscuous," having experienced exactly that

myself.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

And here is to the people of Mississippi,

who say the folks up

North they just don't understand,

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

and they tremble in the shadows

at the thunder of the Klan.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oh, the sweating of their souls

can't wash off the blood from their hands.

|

| | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

For they smile and shrug their shoulders

at the murder of a man.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

And here is to the schools of Mississippi,

where they are teaching all the children that they don't have to

care.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| | |

|

All the rudiments of hatred are present everywhere.

And every single classroom is a factory of despair.

|

| | |

|

|

|

| | |

|

And there is nobody learning

such a foreign word as fair!

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| | |

| | |

|

|

| | |