|

|

After Agee |

Aperture | Fall 1988 AFTER AGEE

J. Ronald Green

Rich and Poor by Jim Goldberg, Random House, New York, 1985, $15.95 paperback. American Pictures: A Personal Journey through the American Underclass by Jacob Holdt, American Pictures Foundation, New York, 1985. (Direct order from American Pictures, P.O. Box 2123, N.Y., N.Y. 10009, $18 hardcover, $15 paperback.) Below the Line: Living Poor in America by Eugene Richards, Consumer Reports Books, New York, 1987, $32 hardcover, $20 paperback. Merci Gonaïves: A photographer’s account of Haiti and the February Revolution by Danny Lyon, Bleak Beauty, copublished with Filmhaus, 1988. (Direct order from Bleak Beauty Books, R.D.l, Box 150 Barclay Road, Clintondale, NY 12515, $17.95 plus $1.50 shipping, paperback.)

Just as novelists after James Joyce have to wonder if there is anything more they can do with the novel form, social documentary photo-and-text bookmakers are confronted with the accomplishment of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, by James Agee and Walker Evans. Its greatness marks what seems to be an expended impulse—to photograph and write about the poor. Actually, that impulse seems exhausted only from the point of view of patriarchy and privilege; Agee and Evans reached the heights from within a dominant sub-culture. Much of the glory of their accomplishments was in bringing cultural responsibility to consciousness in forms worthy of their subject. Part of their responsibility was existential—they were white, male, educated and empowered. The guilt in that responsibility, consciousness of which forms so much of the triumph of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, might not be felt by a woman approaching the same subject. After Agee, social documentary might well be handed over to the disenfranchised—that is the logical consequence of Agee’s work.

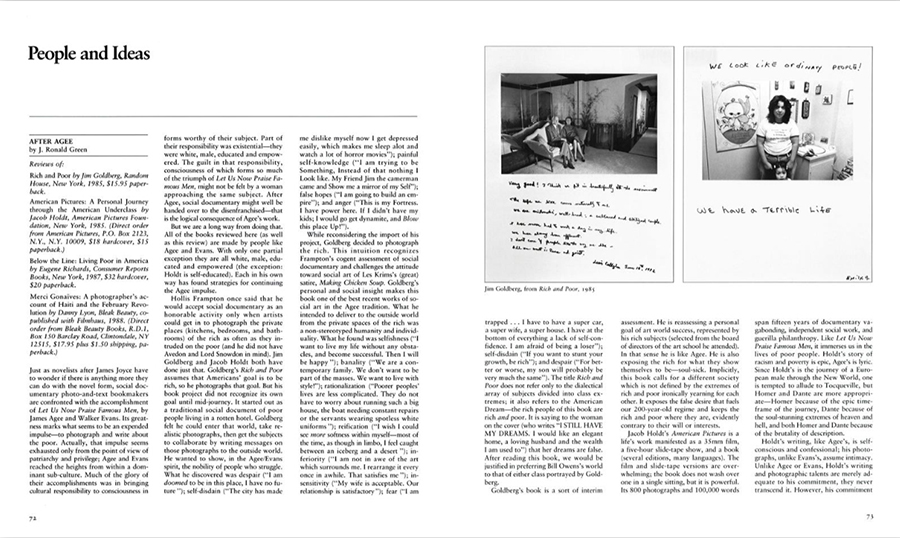

But we are a long way from doing that. All of the books reviewed here (as well as this review) are made by people like Agee and Evans. With only one partial exception they are all white, male, educated and empowered (the exception: Holdt is self-educated). Each in his own way has found strategies for continuing the Agee impulse. Hollis Frampton once said that he would accept social documentary as an honorable activity only when artists could get in to photograph the private places (kitchens, bedrooms, and bathrooms) of the rich as often as they intruded on the poor (and he did not have Avedon and Lord Snowdon in mind). Jim Goldberg and Jacob Holdt both have done just that. Goldberg’s Rich and Poor assumes that Americans’ goal is to be rich, so he photographs that goal. But his book project did not recognize its own goal until mid-journey. It started out as a traditional social document of poor people living in a rotten hotel. Goldberg felt he could enter that world, take realistic photographs, then get the subjects to collaborate by writing messages on those photographs to the outside world. He wanted to show, in the Agee/Evans spirit, the nobility of people who struggle. What he discovered was despair (“I am doomed to be in this place, I have no future ”); self-disdain (“The city has made me dislike myself now I get depressed easily, which makes me sleep alot and watch a lot of horror movies”); painful self-knowledge (“I am trying to be Something, Instead of that nothing I Look like. My Friend Jim the cameraman came and Show me a mirror of my Self”); false hopes (“I am going to build an empire”); and anger (“This is my Fortress. I have power here. If I didn’t have my kids; I would go get dynamite, and Blow this place Up!”). While reconsidering the import of his project, Goldberg decided to photograph the rich. This intuition recognizes Frampton’s cogent assessment of social documentary and challenges the attitude toward social art of Les Krims’s (great) satire, Making Chicken Soup. Goldberg’s personal and social insight makes this book one of the best recent works of social art in the Agee tradition. What he intended to deliver to the outside world from the private spaces of the rich was a non-stereotyped humanity and individuality. What he found was selfishness (“I want to live my life without any obstacles, and become successful. Then I will be happy”); banality (“We are a contemporary family. We don’t want to be part of the masses. We want to live with style!”); rationalization (“Poorer peoples’ lives are less complicated. They do not have to worry about running such a big house, the boat needing constant repairs or the servants wearing spotless white uniforms”); reification (“I wish I could see more softness within myself—most of the time, as though in limbo, I feel caught between an iceberg and a desert ”); inferiority (“I am not in awe of the art which surrounds me. I rearrange it every once in awhile. That satisfies me”); insensitivity (“My wife is acceptable. Our relationship is satisfactory”); fear (“I am trapped ... I have to have a super car, a super wife, a super house. I have at the bottom of everything a lack of self-confidence. I am afraid of being a loser”); self-disdain (“If you want to stunt your growth, be rich”); and despair (“For better or worse, my son will probably be very much the same”). The title Rich and Poor does not refer only to the dialectical array of subjects divided into class extremes; it also refers to the American Dream—the rich people of this book are rich and poor. It is saying to the woman on the cover (who writes “I STILL HAVE MY DREAMS. I would like an elegant home, a loving husband and the wealth I am used to”) that her dreams are false. After reading this book, we would be justified in preferring Bill Owens’s world to that of either class portrayed by Goldberg. Goldberg’s book is a sort of interim assessment. He is reassessing a personal goal of art world success, represented by his rich subjects (selected from the board of directors of the art school he attended). In that sense he is like Agee. He is also exposing the rich for what they show themselves to be—soul-sick. Implicitly, this book calls for a different society which is not defined by the extremes of rich and poor ironically yearning for each other. It exposes the false desire that fuels our 200-year-old regime and keeps the rich and poor where they are, evidently contrary to their will or interests. Jacob Holdt’s American Pictures is a life’s work manifested as a 35mm film, a five-hour slide-tape show, and a book (several editions, many languages). The film and slide-tape versions are overwhelming; the book does not wash over one in a single sitting, but it is powerful. Its 800 photographs and 100,000 words span fifteen years of documentary vagabonding, independent social work, and guerilla philanthropy. Like Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, it immerses us in the lives of poor people. Holdt’s story of racism and poverty is epic, Agee’s is lyric. Since Holdt’s is the journey of a European male through the New World, one is tempted to allude to Tocqueville, but Homer and Dante are more appropriate—Homer because of the epic timeframe of the journey, Dante because of the soul-stunning extremes of heaven and hell, and both Homer and Dante because of the brutality of description.

Holdt’s writing, like Agee’s, is selfconscious and confessional; his photographs, unlike Evans’s, assume intimacy. Unlike Agee or Evans, Holdt’s writing and photographic talents are merely adequate to his commitment, they never transcend it. However, his commitment is virtually total, and that is what makes this a great work of social documentary and a contribution to the Agee impulse. Holdt spent ten years immersed in his subject, created an epic, and, deciding he had gotten it basically right, set about to devote his life to its findings. The book was a bestseller in Europe. He could have made a fortune on it, but instead he hired lawyers to break contracts and pull it out of circulation because of its success. He established a philanthropic foundation to publish and distribute it, using the profits for aid to Africa. There is no doubt it has sold hundreds of thousands fewer copies in the United States than it would have sold with a major publisher, but to Holdt it was more important that the production and distribution be managed by the underclass that the book was intended to help. He has made propagation a priority over propaganda. Holdt’s answer to the moral contradiction, “poverty sells,” is “then let the poor sell it, at least.” Amateurs have control of the whole American Pictures project, beginning with Holdt himself. That amateurism is a great strength. One of the strains of the Agee impulse that offers some promise for social documentary is artistic enfranchisement. Every project that succeeds outside the current system of gatekeeping offers the possibility of mutation, since an uncontrolled voice will be heard by an uncontrolled audience. Holdt says “I have now made so many safe-guards around this book to avoid exploitation, that I have finally come to believe in it as a meaningful tool for change.” Agee had little expectation that his book would effect social change, and he thought it ought to be released on newsprint so it would disintegrate. Compared to Agee Holdt is naive, but less cynical.

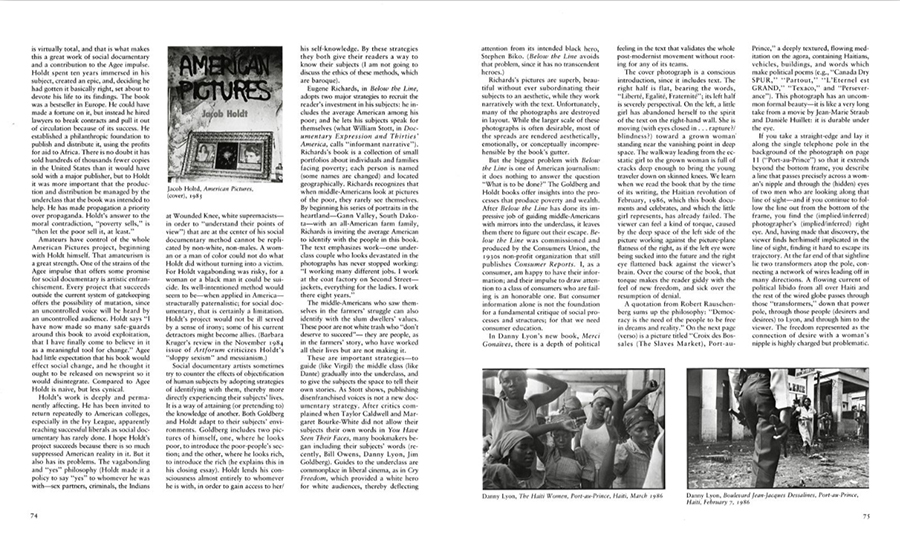

Holdt’s work is deeply and permanently affecting. He has been invited to return repeatedly to American colleges, especially in the Ivy League, apparently reaching successful liberals as social documentary has rarely done. I hope Holdt’s project succeeds because there is so much suppressed American reality in it. But it also has its problems. The vagabonding and “yes” philosophy (Holdt made it a policy to say “yes” to whomever he was with—sex partners, criminals, the Indians at Wounded Knee, white supremacists— in order to “understand their points of view”) that are at the center of his social documentary method cannot be replicated by non-white, non-males. A woman or a man of color could not do what Holdt did without turning into a victim. For Holdt vagabonding was risky, for a woman or a black man it could be suicide. Its well-intentioned method would seem to be—when applied in America— structurally paternalistic; for social documentary, that is certainly a limitation. Holdt’s project would not be ill served by a sense of irony; some of his current detractors might become allies. (Barbara Kruger’s review in the November 1984 issue of Artforum criticizes Holdt’s “sloppy sexism” and messianism.) Social documentary artists sometimes try to counter the effects of objectification of human subjects by adopting strategies of identifying with them, thereby more directly experiencing their subjects’ lives. It is a way of attaining (or pretending to) the knowledge of another. Both Goldberg and Holdt adapt to their subjects’ environments. Goldberg includes two pictures of himself, one, where he looks poor, to introduce the poor-people’s section; and the other, where he looks rich, to introduce the rich (he explains this in his closing essay). Holdt lends his consciousness almost entirely to whomever he is with, in order to gain access to her/ his self-knowledge. By these strategies they both give their readers a way to know their subjects (I am not going to discuss the ethics of these methods, which are baroque). Eugene Richards, in Below the Line, adopts two major strategies to recruit the reader’s investment in his subjects: he includes the average American among his poor; and he lets his subjects speak for themselves (what William Stott, in Documentary Expression and Thirties’ America, calls “informant narrative”). Richards’s book is a collection of small portfolios about individuals and families facing poverty; each person is named (some names are changed) and located geographically. Richards recognizes that when middle-Americans look at pictures of the poor, they rarely see themselves. By beginning his series of portraits in the heartland—Gann Valley, South Dakota—with an all-American farm family, Richards is inviting the average American to identify with the people in this book. The text emphasizes work—one underclass couple who looks devastated in the photographs has never stopped working: “I working many different jobs. I work at the coat factory on Second Street— jackets, everything for the ladies. I work there eight years.” The middle-Americans who saw themselves in the farmers’ struggle can also identify with the slum dwellers’ values. These poor are not white trash who “don’t deserve to succeed”— they are people, as in the farmers’ story, who have worked all their lives but are not making it. These are important strategies—to guide (like Virgil) the middle class (like Dante) gradually into the underclass, and to give the subjects the space to tell their own stories. As Stott shows, publishing disenfranchised voices is not a new documentary strategy. After critics complained when Taylor Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White did not allow their subjects their own words in You Have Seen Their Faces, many bookmakers began including their subjects’ words (recently, Bill Owens, Danny Lyon, Jim Goldberg). Guides to the underclass are commonplace in liberal cinema, as in Cry Freedom, which provided a white hero for white audiences, thereby deflecting attention from its intended black hero, Stephen Biko. (Below the Line avoids that problem, since it has no transcendent heroes.) Richards’s pictures are superb, beautiful without ever subordinating their subjects to an aesthetic, while they work narratively with the text. Unfortunately, many of the photographs are destroyed in layout. While the larger scale of these photographs is often desirable, most of the spreads are rendered aesthetically, emotionally, or conceptually incomprehensible by the book’s gutter. But the biggest problem with Below the Line is one of American journalism: it does nothing to answer the question “What is to be done?” The Goldberg and Holdt books offer insights into the processes that produce poverty and wealth. After Below the Line has done its impressive job of guiding middle-Americans with mirrors into the underclass, it leaves them there to figure out their escape. Below the Line was commissioned and produced by the Consumers Union, the 1930s non-profit organization that still publishes Consumer Reports. I, as a consumer, am happy to have their information; and their impulse to draw attention to a class of consumers who are failing is an honorable one. But consumer information alone is not the foundation for a fundamental critique of social processes and structures; for that we need consumer education. In Danny Lyon’s new book, Merci Gonaïves, there is a depth of political feeling in the text that validates the whole post-modernist movement without rooting for any of its teams. The cover photograph is a conscious introduction, since it includes text. The right half is flat, bearing the words, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité”; its left half is severely perspectival. On the left, a little girl has abandoned herself to the spirit of the text on the right-hand wall. She is moving (with eyes closed in . . . rapture?/ blindness?) toward a grown woman' standing near the vanishing point in deep space. The walkway leading from the ecstatic girl to the grown woman is full of cracks deep enough to bring the young traveler down on skinned knees. We learn when we read the book that by the time of its writing, the Haitian revolution of February, 1986, which this book documents and celebrates, and which the little girl represents, has already failed. The viewer can feel a kind of torque, caused by the deep space of the left side of the picture working against the picture-plane flatness of the right, as if the left eye were being sucked into the future and the right eye flattened back against the viewer’s brain. Over the course of the book, that torque makes the reader giddy with the feel of new freedom, and sick over the resumption of denial. A quotation from Robert Rauschenberg sums up the philosophy: “Democracy is the need of the people to be free in dreams and reality.” On the next page (verso) is a picture titled “Croix des Bossales (The Slaves Market), Port-auPrince,” a deeply textured, flowing meditation on the agora, containing Haitians, vehicles, buildings, and words which make political poems (e.g., “Canada Dry SPUR,” “Partout,” “L’Eternel est GRAND,” “Texaco,” and “Perseverance”). This photograph has an uncommon formal beauty—it is like a very long take from a movie by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet: it is durable under the eye.

If you take a straight-edge and lay it along the single telephone pole in the background of the photograph on page 11 (“Port-au-Prince”) so that it extends beyond the bottom frame, you describe a line that passes precisely across a woman’s nipple and through the (hidden) eyes of two men who are looking along that line of sight—and if you continue to follow the line out from the bottom of the frame, you find the (implied/inferred) photographer’s (implied/inferred) right eye. And, having made that discovery, the viewer finds her/himself implicated in the line of sight, finding it hard to escape its trajectory. At the far end of that sightline lie two transformers atop the pole, connecting a network of wires leading off in many directions. A flowing current of political libido from all over Haiti and the rest of the wired globe passes through those “transformers,” down that power pole, through those people (desirers and desirees) to Lyon, and through him to the viewer. The freedom represented as the connection of desire with a woman’s nipple is highly charged but problematic. The photograph of “An out-of-uniform Tonton Macoute with an Uzi machine gun harassing a crowd” (p. 16) is formally similar, but in this case the sightline with which the photographer aligns himself is the gesture of an outstretched hand and a gun that seem directly to control the crowd. The image of connectedness here is explicitly male domination and control. Many other photographs suggest the vulnerability of women under that control. “Boulevard Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Port-au-Prince” (p. 30) is shot at crotch level from behind a uniformed man with a pistol; it shows a woman trying to cross the street with her “hands up.” The sign over her head reads “quincaillerie,” French for “hardware” but also slang for “shooting irons” from the French comic book series, Lucky Luke. With this book, Lyon has returned to the genre of his first photographic work—liberation journalism. In the early sixties, he was the first staff photographer for the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at the start of the civil rights movement in the South. His 20,000-word text in Merci Gondives is a new-journalistic report of an important news event. Lyon compares Haiti, 1987, with Georgia, 1962. “In the South, the movement sang a system down; in Haiti they danced a dictator out of his palace. Gonaïves, that dry, dusty, forgotten town, two hours from Port-au-Prince, couldn’t but remind me of another quiet town a few hours south of Atlanta—Albany, Georgia.” Lyon considers Haiti his responsibility, just as he as a Northerner considered Georgia his responsibility; just as he as a free man considered Billy McCune, a prisoner on death row in Texas, his responsibility. Throughout Merci Gondives, Lyon blames the United States for Haiti’s problems, and specifically for the failure of the revolution. He finds U.S. policy ironic, given the craving of the Haitians for American democracy and their hatred of “communists.” Lyon reports that after the new government began to disintegrate, the kind of aid the U.S. decided to give was military: “Of all the things Haiti needs, an army is not one of them . . . The only thing I ever heard of the Haitian army shooting is the Haitian people.” What the army is really there for, he implies, is to protect the extreme separation of wealth and poverty evidenced by concrete visions of abstract materialism: “. . . Baby Doc drove himself and his family to the airport at 3:30 in the morning in a white BMW 730Í. His wife, a mulatto named Michèle Bennett, owned the BMW franchise, and it was common in Port-au-Prince to see these fabulous high-tech road machines parked amid the mud and misery of the market.” Since Americans are inured to such surrealism, since it is our way of life, Lyon’s photographs try to reach into us in other ways, trying to make our blood rush the way these people and this revolution made his blood rush. For that, the text is necessary. Evans’s photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men are great examples of his aesthetic, whether Agee is there or not, but Agee’s text modulates and elevates Evans’s accomplishment in ways Evans always appreciated. The photograph on the back cover, of Lyon embracing a happy reveler at the height of the revolutionary celebration, could be seen as another image of the white liberal hero of the Cry Freedom variety. In fact, it is the image of an epiphany for Lyon, which this book is about. Early in the text, he describes this moment: “Marchers filled the streets and threw bread to us and to everyone. We raised our fists and yelled ‘Liberté!’ ‘Liberté!’ the crowd yelled back. ‘Américain!’ we yelled. ‘Américain!’ they yelled back. And then they fell into our arms and we held close sweet liberty.” But it is a more somber note on which Lyon chooses to close the book: “And so all those Haitian people who named their streets for Truman, Lincoln, King and John Brown, who sang and danced and waved those precious dime-store American flags while we smiled and whispered ‘elections’ into their ears, have been betrayed. It seems that in order to maintain a democracy in our country, Haitians will lose the chance to have one in theirs.” The young woman in the photograph facing the closing text resembles our Statue of Liberty, but marks the end, rather than the beginning, of a political possibility. She is the image of bleak beauty that drives Lyon’s and Agee’s art.

|