Book 6, pages 76-83

Dear Angela,

I've finally gotten to a home with a typewriter, which gives me a chance to

tell you a little bit about what has happened since we were together last. I

have ended up living with two young white women here in Greensboro. They are

treating me as if I had gone to heaven, which has an overwhelming effect on me

after the last couple of weeks of a helter-skelter existence. One of them,

Diane, is a model and a criminologist of the leftist kind, and likes my

pictures so much that she will do everything in her power to get me money to

buy more film. She has very good connections and with her charm and her looks

it is easy for her to conjure up money for good causes. For example, she has

just collected over $3,000 to get a lawyer for a Vietnam deserter who is in

prison. Since she can't go around to the same affluent homes right after she

has just tapped them, I'll have to wait at least half a year, but she has

promised that by then she will collect some money for me by telling people that

it is to be used for a home for handicapped children or something. I think it

sounds a little unsavory, but she says that may be it will teach them that it

is the government's job to provide such human rights, and not something which

should be left to private charity. Well, I doubt that she will really be able

to collect anything for me.

Every time I have had that kind of small hope I have been disappointed. I guess I still have to be content with selling blood and with the small gifts of money I get on the road by entertaining people with my pictures and experiences. Last week I had an income of nine dollars, which is the best ever: five dollars from an interested salesman who picked me up, two dollars from a black woman in Tony's father's grill, and two dollars from a guy in West Virginia who found my picture of the junkies with the Capital in the background interesting and bought it. Included in the deal was his lunch bag which contained three chicken legs. Now, since I have had these prints made, it makes me so happy every time I experience that kind of positive reaction. But it also scares me a little sometimes. In one place a woman started crying when she saw my pictures, and I didn't know what in the world to do. It is strange with Americans. They have lived in the midst of this suffering all their lives without giving it a thought, and then suddenly, when they see it frozen in a photograph, they can begin crying. Some accuse me of beautifying the blacks, though if anything most people here in the South probably admire my pictures for that reason. I just don't understand it; I photograph them exactly the way I see them, and a photograph doesn't lie, does it? But the more I ponder over it, the more I come to realize that this parallax shift in the way we see blacks must be due to the fact that they have lived in this master-slave relationship for such a long time that they simply are not capable of seeing blacks as human beings, but can only see those sides in them which confirm their "slave nature." But when Southern whites nevertheless react positively to my pictures, I believe it is because in reality they are unhappy about seeing with these "master"-eyes. They are longing to become human, and the moment I can "prove" to them that blacks are human and not slaves, eternal children, or subhuman (or what have you), this makes them themselves human and no longer masters or super-humans or whatever. If I don't interpret it this way, how then should I explain that even the worst racists down here give me money once in a while, although mumbling something or other about how they think "it is funny how I run around photographing niggers." I have to admit that it often seems difficult when I try to depict the master-slave relationship as an institution not to end up depicting it as if people in this system really have this "nature."

Often I feel that my own

view becomes contaminated by this sneaking poison in the South, because I put

great emphasis on respecting the dignity of these people, especially the older

people. They have lived in this master-slave tradition all their lives, and

both for the blacks and for the whites I feel that it would do violence to them

to try to tear them out of this tradition (though the coming generations

absolutely must avoid this crippling of the mind). I, therefore, never try to

impose my views on them, but try to understand theirs and to learn from them.

Precisely because from the beginning I respect their dignity, I often build up

such strong friendships with them that through these friendships I can get

them to respect and to learn from my point of view. As a vagabond in the South

it is absolutely essential to be able to communicate through friendship instead

of inciting hostility and confrontation. But if you are able to do that - and

even receive constant love and admiration, as I am fortunate enough to, or

almost daily hear sentences like "I envy you" or "Do you know that you are a

very lucky person?" - then you are walking a thin line where you easily get

mired down in the mud. This gap between my utopian reality and my actual

reality (which we have talked about before) is just as difficult to bridge as a

river that constantly grows wider and wider, so that you slowly lose sight of

the other bank, while you little by little drown in mud on your own bank.

However, it seems that if you interpret "the mud" on this side of the river

correctly (that is, if you dig down to people's deepest longings, even if they

still do not see the connections between it all), then they will allow you to

build an ivory tower so tall and beautiful that you can sit up there and tell

people down on the bank below you how nice the other bank looks. But since you

yourself do not have any personal contact with the other shore - a contact

which could have changed your own character and entire soul - there is no way

you can communicate your vision to the people below, since they see no evidence

that you yourself have actually been "touched" or changed. Besides, they are

busy enough just trying to keep their heads above the mud. They therefore soon

forget the message of your story, but find the story itself so interesting,

that they allow you to build the ivory tower even higher and to reinforce it

and beautify it. In frustration and depression at not being able to communicate

your message down to them, you get more and more insecure and have a greater

need for recognition and admiration of the ivory tower you have built - even

more than for their recognition of why you originally wanted to build it.

Finally you become so confused and insecure that only their recognition of the

tower itself, its beauty and form, counts for

you. And you build it higher and higher, until you get up to those cynical

heights where you can no longer really see either your own or the opposite

bank, and they begin to look alike. Moreover, you have now reached such a

height that you lose touch with the people on your own bank as well and decide

to send your ivory tower out in book form so people have something to entertain

them-selves with there in the mud. Though what you

really started out to do was build a bridge to the opposite bank, you end up

building a tower on your own bank. Instead of helping people out of the mud,

you are in reality making their situation worse in that you have now given them

something either to be happy about or to cry over right where they are and thus

reinforced this muddy river bank. Moreover, your ivory tower is morally

reprehensible precisely because it is built on a foundation of mud: your

artwork is the direct result of the exploitation of the people you originally

had it in mind to help, and the higher your tower becomes, the further you

remove yourself from their suffering. It is thoughts like these which

have made me increasingly depressed in the last months. I constantly hear

people saying, "How I envy you that you can travel among the blacks like that,"

or the like, and I realize that I have already distanced myself so far from the

mud puddle. And it is when I realize, in spite of this yearning, the

impossibility of fashioning a bridge, that I can become so desperate that I

feel that the gun ought to be my real weapon rather than the camera. But

immediately then the question arises as to which direction I would shoot, since

I - as you know - feel that everyone is equally mired in this river bank. Where

is the rainmaker who created the mud puddle? And therefore I keep on wading

here in the mud, trying only to keep my camera clean enough that it can

register the victims - without really believing myself that it will ever be of

any use.

Well, but what I really wanted to tell you was a little about what has happened since we parted. One of the first people, who picked me up was a well-off Jewish businessman (Jews are always picking me up to thank me because Denmark saved a number of Jews during the war, though I wasn't even born at that time and though I increasingly feel myself just as much American as Danish). He did not really feel like taking me home, since he was completely knocked out, partly because his business was going badly and partly because his brother was dying of cancer. He was strongly under the influence of tranquilizers, but he realized that he needed someone to talk to and therefore took me home to his wife. It was a very powerful experience for me. Completely shaken, they waited from moment to moment for a call from the hospital saying that the brother was dead, and against this gloomy background my pictures made an enormously strong impression on them. When I took off the next morning, they thanked me very much and he tried to give expression to the experience with tears running down his cheeks by quoting "I used to cry because I had no shoes until I met a man who had no feet." Before I left, he gave me a bag with 15 rolls of film.

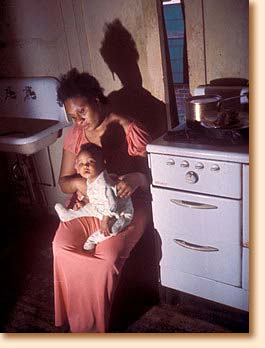

From Philadelphia I then went to Norfolk to stay overnight on my way south. I walked around the ghetto looking for a place to stay and talked with some of the old women who were going around with their little handcarts to collect firewood in the ghetto's ruins. One of them told me that she could now afford only four pig's tails a day instead of five because of inflation. It was strange to hear that in the shadow of the world's largest naval base. I ended up staying with a 32-year-old single black mother. She was not the type who normally invites me in, but her uncle had taken me to her apartment to show me how her ceiling was leaking, in the hope that I was a journalist who could get the city to repair it.

When he left, I got on with the woman so well that

she let me stay. She had just had her first child and it was a wonderful

experience to see her spend almost every minute tending it. I sat for hours

watching. She was also deeply religious, and when the baby was sleeping, we sat

praying together or she would read aloud to me from the Bible while she held my

hand. She would sit there for a long time staring up at a picture of Jesus

right under the dripping ceiling with a look so intense and full of love that I

was very moved. After a couple of days in town, I went down to Washington,

North Carolina, arriving just after nightfall. I walked around all evening

looking for shelter for the night, but everyone was scared of me, thinking that

I was a "bustman" (plainclothes cop). First a man said I could stay in his

uncle's house on the sofa. He took me to an old red-painted shack which was

filthy and without light. His uncle came out with an oil lamp in his hand and

was extremely angry and used his stick to demonstrate it with, but we managed

to get in and I got some old chicken legs on a dirty plate in that corner of

the shack which served as the kitchen, although there was no running water. But

the old man was still mad and it got worse and worse, and finally he threw me

out with his stick. He wasn't going to have any whites in his house, he

thundered. Then he took big boards and planks and nailed them up in front of

the windows and doors for fear that I would break in, and walked off into the

darkness, still screaming and yelling. He had no trust in whites. Further down

the street a woman called from a porch, offering to share a can of beer. Later,

while I was sitting trying to converse with her sick husband, who was in a

wheelchair and was not able to talk, I noticed her gazing at a picture of

Christ on the wall. A while later she indicated that I should come into the

incredibly messy bedroom in the back. I wondered what the husband was thinking

about that, unable to make a move. In there she first embraced me, staring at

me with big watery eyes. Then suddenly she fell down at my feet, and while she

held my ankles she kissed my dirty shoes, whispering, "Jesus, Jesus."

I have, as you know, often been "mistaken" for Jesus among Southern blacks

because of my hair (which is one

reason I keep my silly braided beard), but in most cases their sense of humor

allows us to laugh together at their Jesus-identification. You will probably

see it as yet another example of the "slave's" identification with or even

direct infatuation with the "master." Whatever is behind it, it is probably of

some help to me in breaking through the race barrier. But in such a shocking

situation as this, I simply had no idea of what to say, as I didn't know if it

would be wrong to shake her out of her religious experience. I searched for a

fitting Bible quote... the futility of the Samaritan woman drinking from

Jacob's well... but I couldn't get a word to my lips. I stood there for more

than an hour before I had the courage (cruelty) to break her trance. It was

such a strong experience that I didn't feel I could stay there for the night.

As I wandered around the streets again, I met around ten o'clock a young black

woman who must have been a little drunk, for she asked right off if we couldn't

be friends (unusual from my experience of black women in the South). She said

that if l could find a place to stay that evening, she would come stay with me.

I doubted it would work, but we walked into one of those Southern "joints" (speakeasies) and

talked to her cousin about possible places. All of a sudden she started kissing

me wildly all over and asked sweetly, "Are you a hippie?" I said no, but she

didn't get it. Actually, this joint was not the safest place to hang out.

Around us in the dark we could dimly see 15 to 20 "superflies." A couple of

them came over and warned me in a friendly tone that it was a dangerous place,

but I answered with conviction, "I ain't scared of nothing," which usually

impresses them, since they themselves are scared of their own shadow in these

joints.

But then all hell broke loose. Someone must have told the guy the woman was

"shacked up with" about our project, for suddenly he came running in with a big

knife and went first for his woman. Luckily he didn't use the knife, but he

beat the poor woman to pieces, hit her in the face and gave her a real beating,

worse than I have seen in months. I must have been pretty cold-blooded that

evening, now that I think of it, because I immediately pulled out my camera and

tried to attach the flash, but just then two guys came running over and grabbed

me:

"You better get the hell out of here. When he's done with her, he's gonna go

after you." And they practically carried me out of the place. I never saw the

woman again. Though I have seen this kind of thing so often, I was a little

shocked, because in some way I myself had been the cause of it. It is as if you

can't attain deep human relationships without always becoming either victim or

executioner. For the most part I am of course a victim, but since I always try

to go all out with people, it happens now and then that I cross the invisible

line separating the victim from the executioner. This I hate, because I am then

forced to take matters into my own hands instead of letting other people

direct things. I didn't get that far on this night, though, and I'm beginning

to fear that I have gradually become so hardened that I have lost my own will

power. Perhaps it was this thought that nagged me, and made me react

differently than usual later that night. For when I had walked around for yet

another couple of hours, I finally managed to get a roof over my head with two

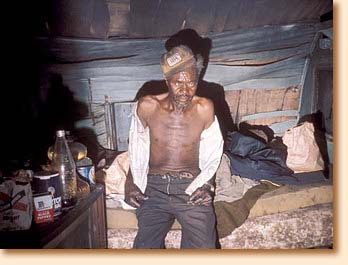

old bums. They were drunk as hell, and there was an incredible mess. They

couldn't even afford kerosene, so there was no light. We were all three supposed to sleep in one bed. There were inches of dirt underneath it

and every 25 minutes one of us had to get up to put wood on the stove, since it

was very cold. At first I was sleeping between them, but then I realized they

were both homosexual. So I moved over next to the wall so I would only have one

to fight off, but he turned out to be the most horny. In that kind of situation

I usually resign myself to whatever happens, but this night I didn't feel like

it, perhaps because of the earlier experience in that joint.

He was what you might call a "dirty old man" with stubble and slobber, but that was not the reason. I have been through far worse things than that. I had probably just gotten to the point where I was tired of being used by homosexual men. I hate to hurt people, but I suppose that this night I was trying to prove to myself that I had at least some willpower left. So I lay on my side with my face to the wall. But he was clawing and tearing so hard at my pants that I was afraid they were going to rip, and since it is the only pair I have, I couldn't afford to sacrifice them. So I turned around with my face toward him, but he kept at it and pressed his big hard-on against my ribs and began to kiss me all over – kisses that stunk of Boone's Farm apple wine. The worst was that he kept whispering things in my ear like, "I love you. I love you. Oh, how I love you." Well that was maybe true enough at that moment, but it drove me crazy to listen to it. As you know, I feel that especially among black men this word has been overused. I don't think it is something you can say the first night you go to bed with someone. The only thing missing was him saying, "Oh, you just don't like me because I am black." But luckily I was spared that one. Well, he finally got his pacifier, hut that did not satisfy him, as he was the kind of homosexual who goes for the stern. He just became more and more excited and finally became so horny that I felt really guilty, but still I didn't give another inch. He tried and tried. Finally he destroyed the beautiful leather belt you gave me that time when I couldn't keep my pants up anymore. It made me so damned mad that I grabbed his big cannon with both hands and turned it hard toward the other guy who was snoring like a steamship. "Why don't you two have fun with each other and leave me in peace. I want to sleep." But it didn't help, so the struggle continued all night with me every five minutes turning the cannon in the other direction (about four times between each new load of firewood). Finally the guy left around eight o'clock and I got a couple of hours of sleep. Later in the day I met him in the local coffee bar. He came over and asked if I was mad at him. I said, "Of course not, we are still good friends. I was just so damn tired last night." He was so glad that he began to dance around, making everybody there laugh at him. He was one of those who are outcast among both blacks and whites. I was very sad, because I felt that I had destroyed something inside myself. I felt a deep irritation that I had not been able to give him love. In his eyes, I was a kind of big-shot and it would have made him happy if I had given myself fully. There was just something or other inside me that went "click" that night, so the whole next day I felt a deep loathing of myself. I am constantly finding many shortcomings in my relationships with people, but the worst thing is when my shortcomings hurt such people, who are already hurt and destroyed in every possible way by the society surrounding them.

If I could not constantly give such losers a little love, I simply would not be

able to stand traveling as long as I have.

The only thing that has any meaning for me in my journey is being together with

these lonesome and ship-wrecked souls. My photographic hobby is really, when

all is said and done, nothing more than an exploitation of the suffering, which

will probably never come to contribute to an alleviation of it. But still I

can't stop registering it, because in some way or other it must get out to the

outside world.

That strength I get by being together with these extreme losers, and the love I

often receive from them, is what in spite of everything gives me a slender hope

that my pictures will be able to speak even to society's winners. That I

nevertheless reacted so negatively that night may also stem from the fact that

I recently had a similar experience which hurt me deeply. It was the same day

that I left you in Plainfield. One of the first ones who picked me up on the

road in New Jersey was a white guy in his fifties or sixties. He immediately

began talking about how he had always been the black sheep in the family and

even used the expression "dirty old man" about himself. Such self-hatred I meet

so often among older homosexuals. He asked me to go home with him and talk with

him, and I couldn't say no, although I did have in mind to get to North

Carolina the same day. After we had talked all day, he took me in the evening

to the movie theater where he was the projectionist. He was running a John

Wayne movie of the usual kind. In the middle of the film

he began to stroke my thighs. It didn't really surprise me, but I found

it so ironic that the whole time he stood there commenting on the film,

especially the two-fisted scenes, cheering John Wayne on: "Give it to 'em,

knock 'em out" etc. How could he identify to such a degree with John

Wayne's frightening universe of male chauvinism and macho oppression, which

more than anything else had oppressed him throughout his life and given him

this violent self-hatred? During the intermission I walked around in the large

shopping center where the cinema was located. No matter where I went,

sales-stimulating plastic music from the loudspeakers followed me, and I

suddenly felt a terrible disgust with America, which I erroneously equated with

my John Wayne experience. But in the midst of this disgust I felt that even

though these people are to such an extent their own oppressors, it had to be

possible to get through to them and tear them loose from this sadomasochistic

pattern. In the evening, when I came home to him, I tried to see all the beauty

in him. It was not easy, for he was indeed of that type whom society has

condemned as repulsive and obscene, but with all the energy I had just received

from my stay with you, I had such a surplus that night, that I really believe

that I felt glimmerings of love for him. But then the thing happened which was

to defeat me. In the heat of the night in bed my wig slipped off, and out fell

my long hair. I could clearly see his astonishment and distaste, but he tried

to hold it back and mumbled something in the way of: "Well, at least you

aren't a dirty hippie." But from that moment our relationship was smashed to

pieces, and I was not able to get him to open up again. He would probably have

preferred to kick me out right there and then, but I was allowed to stay since

it was pouring that night. Although he was short and had short, stumpy legs, he

was so fat that I had to sleep all the way out on the edge of the bed and could

only keep from falling off by supporting myself all night with one hand on the

floor. I therefore couldn't sleep, hut just lay there thinking about how

strange it is that people can have such strong prejudices that they even take

them to bed with them. Since it was still pouring the next morning, I wondered

if I should stay another day and try to break through the ice, but that was

obviously not what he had in mind. Almost without mumbling a word he drove me

out to the main road near Milltown, where I stood in the pouring rain for the

next seven hours, since, as you know, people will never pick you up when you

need it most. You must be crazy standing out in the rain, they

think. It was then that the Jewish businessman at long last fished me up. As

you can understand, I was almost as far down as he was, though I didn't tell

him about my depressing experience.

Well, I will tell you more about

Washington, N.C., in a later letter and just finish off by saying that I am now

on the way out of the depression I was in over you back then, though the memory

of you still hangs like a heavy dark cloud over my journey. It is still a

mystery to me how I could be so hurt by our relationship, and why it took the

direction it did. Although you are younger than me, it nevertheless developed

into something of a mother-son relationship, which I in no way could have

imagined at the beginning of my love for you. Your strength and wisdom did not

let you be seduced into a relationship as unrealistic as ours would have

become. You belong to the black bourgeoisie, and though I loved to fling myself

in your luxurious upholstered furniture, I ought to have realized right away

that it wasn't my world.

You were fascinated by my vagabond life and supported

me in my project from a feeling of black pride, but your pride was nevertheless

threatened by the world I represented. Right hack from when your ancestors were

given an education by the slave master, your family has kept up this class

difference, and I can't help feeling that this mile-wide psychological gap you

have been brought up to feel between yourself and that ghetto I normally move

around in, was what actually destroyed our relationship. But no matter how I

analyze it and try to understand it, it is hard for me to accept that it should

end like that between us. The suffering I went through in your house, I never

wish to experience again, but as a vagabond, I have nevertheless become so much

of a fatalist that I believe it has been good for something, and that it will

make it easier for me to identify with and become one with other people's

suffering, though of course the suffering I see around me in this society is of

a far more violent nature than what I experienced with you. Even so, I will

still use the word "suffering" to describe the process I went through with you.

Without this suffering you couldn't have knocked me so much off balance.

From

the moment you realized that we weren't right for each other, and your love

cooled down to a certain aloofness, I experienced a growing desperation in

myself. I am by nature not very aggressive, as you know, and not even very

self-protective, but confronted with your beginning rejection, I experienced an increasing aggression which became

more and more

unbearable. With all your psychological insight, you probably sensed it. At any

rate, it blazed up that night when I moved into your bed without being invited,

thereby breaking my fixed principle of traveling: never violate people's

hospitality. But if I am really to illustrate the psychological desperation I

felt over you in my love, a desperation stronger than any I have ever felt

toward a woman, then I can't do it better than by letting W.E.B. Dubois'

well-known quotation describe my frame of mind:

It is difficult to let others see the full psychological meaning of caste

segregation. It is as though one, looking out from a dark cave in a side of an

impending mountain, sees the world passing and speaks to it; speaks courteously

and persuasively, showing them how these entombed souls are hindered in their

natural movement, expression, and development; and how their loosening from

prison would be a matter not simply of courtesy, sympathy, and help to them,

but aid to all the world. One talks on evenly and logically in this way but

notices that the passing throng does not even turn its head, or if it does, glances curiously and walks on. It gradually penetrates the minds of the

prisoners that the people passing do not hear; that some thick sheet of

invisible but horribly tangible plate glass is between them and the world. They

get excited; they talk louder; they gesticulate. Some of the passing world stop

in curiosity; these gesticulations seem so pointless; they laugh and pass on.

They still either do not hear at all, or hear but dimly, and even what they

hear, they do not understand. Then the people within may become hysterical.

They may scream and hurl themselves against the barriers, hardly realizing in

their bewilderment that they are screaming in a vacuum unheard and that their

antics may actually seem funny to those outside looking in. They may even, here

and there, break through in blood and disfigurement, and find themselves faced

by a horrified, implacable, and quite overwhelming mob of people frightened for

their own very existence."

I don't think that this picture of my state of mind during hose days is very

much exaggerated, so insane was my infatuation. But it amazes me that at such

an early stage you could see how lopsided our relationship was. A marriage

between us, when all is said and done, would have ad this invisible glass

barrier between us, with me inside the cave, which I have devoted so much of my

life to, and with you on the outside. With all your upper-class nature you

could never have lived the life I lead in the cave, and which I try to show to

the outside world with my pictures. I know that in my mind in one way or

another I will always be inside the cave, while you know as well as I do that

you will always be on the outside in spite of a certain insight into the cave.

Every time I dug myself too deeply into the cave and felt lost, you could

always with your wisdom and deep human insight explain it to me and put

everything into perspective. It was therefore not surprising that you more and

more became a kind of mother for me in spite of all my resistance. The thing I

am afraid of is that in spite of your understanding of the cave you have still

been so marked by your class that at the critical point when the glass barrier

is broken, when all is said and done, you will be found among the horrified and

implacable mob. To avoid that, we have to keep working together. If a marriage

between us was unrealistic, and for me in the cave inevitably destructive, it

is at any rate not unrealistic that there be a deep friendship between us. If

you will continue to support and advise me, we can in such a friendship

gradually break down that glass barrier and build up a relationship of such

strength and value as our two races will have in post-racial America, when our

common struggle is over. Through our continued friendship I can thus build the

bridge over the river, so that my work will not just become one white man's

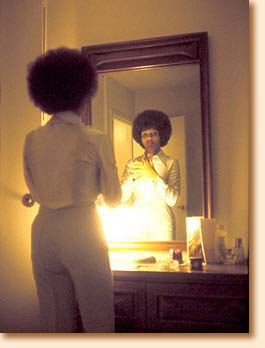

ivory tower. My love for you still has the character of infatuation more than

of friendship. Your beauty and soft, big afro, your gentle deep (and motherly)

voice and your sweet lips that used to kiss me awake in the morning still

torment me in my thoughts. But as soon as I am out of this cave-like state of

mind, perhaps in only a few months, I will be back in Plainfield, and we can

begin to build up our friendship - a friendship without which we will never

succeed in breaking down the glass barriers and building a bridge to a new and

beautiful America. Until then, you remain my beloved, but distant and

unattainable, Angela.

With love Jacob

Copyright © 2005 AMERICAN PICTURES; All rights reserved.